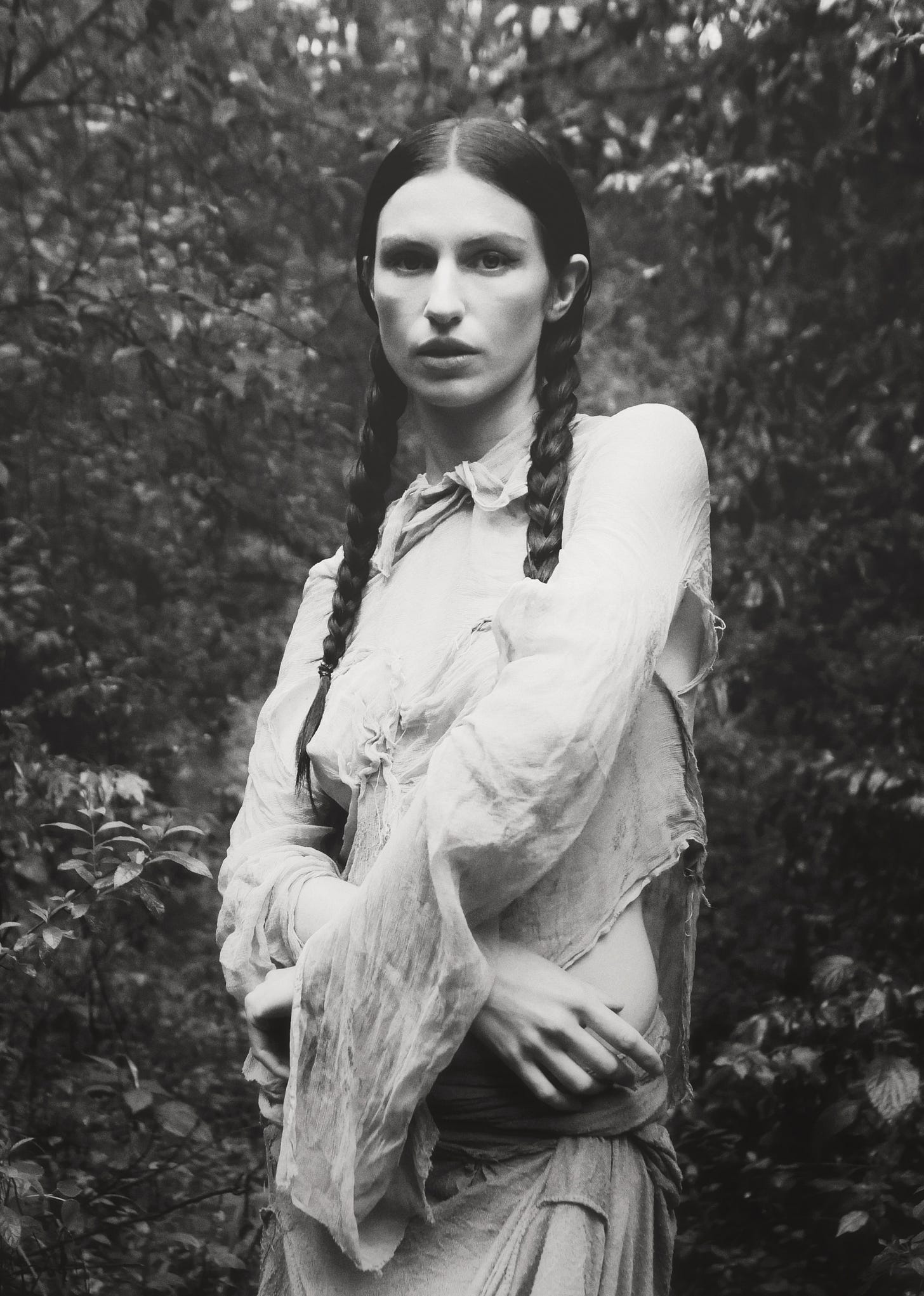

Tali Lennox is Seeking Transcendence

The artist joins me to discuss sex, spirituality, and the sublime

Happy Friday! Today’s post is the second edition of my column Figure Study, co-published by Pleasure-Seeking and Elephant Magazine. I’m joined by the talented Tali Lennox—one of my favorite artists, and a fascinating thinker—to discuss her latest show, the relationship between sex and spirituality, and near-death experiences.

“I mean, my paintings aren’t necessarily about desire, but I think I’m painting what I desire,” says the artist Tali Lennox. We’re sitting in a quiet garden in Brooklyn, surrounded by spotted lanternflies that neither of us has the heart to kill, and talking about her latest solo exhibition, Sulis & The Wreck, at Galerie Sebastien Bertrand.

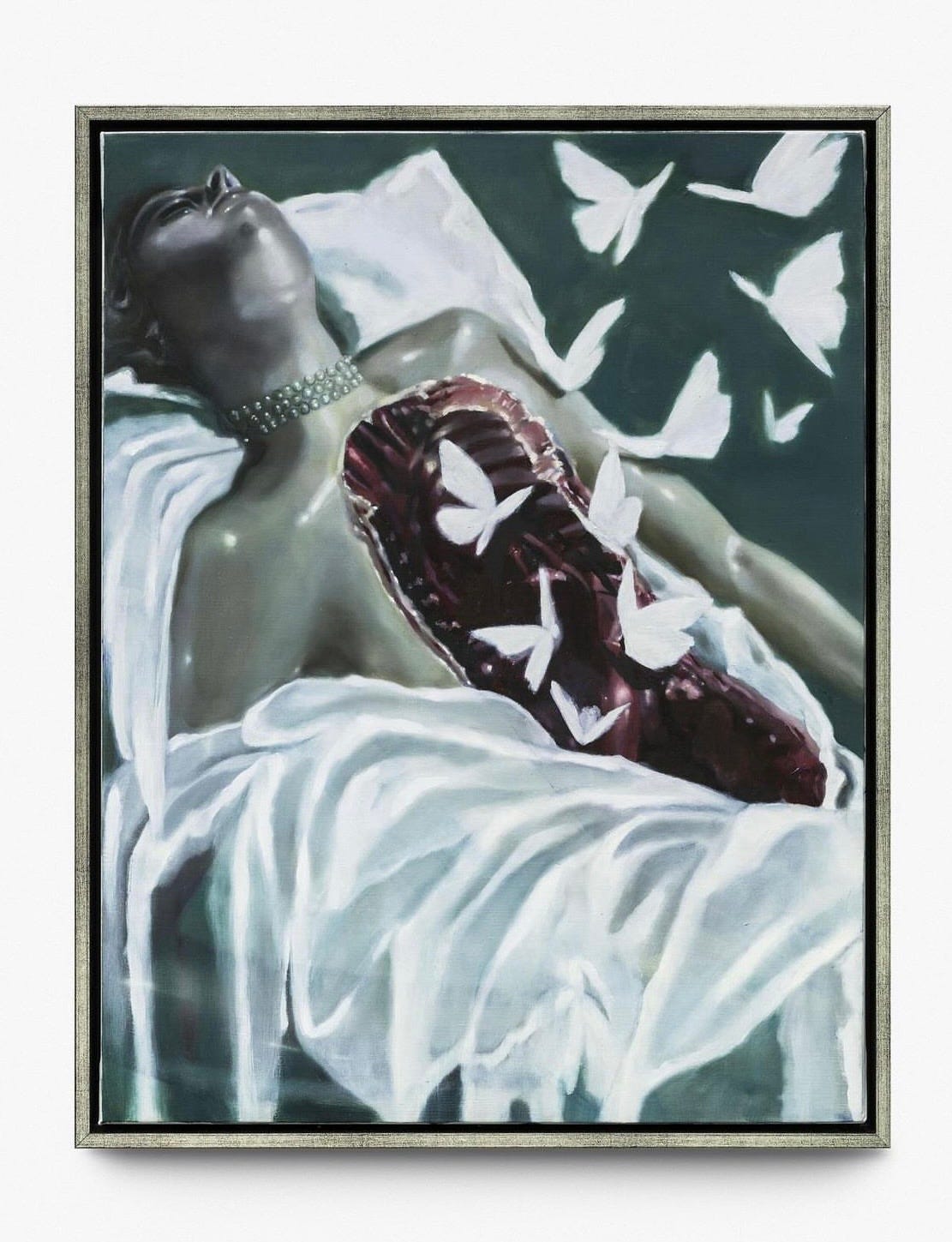

Like much of Tali’s work, the show explores themes of transformation, spirituality, and catharsis. Her paintings are dreamlike and surreal, full of evocative symbolism that’s hard to pin down. But it hasn’t always been this way; for years, Tali painted portraits before a near-death experience changed her orientation toward life. Her work, too, transformed—channelling inspiration from mythology and folklore, and inviting viewers into a space between realms.

Tali’s work isn’t explicitly about sex, though it is about pleasure-seeking and the ways we find ourselves through it. Like creativity and spirituality, eroticism allows us to inhabit a space outside the ordinary: between the known and unknown, body and spirit, self and other. Sex is a way of bridging the inner and outer worlds, of experiencing transcendent pleasure, and surrendering the ego—or, as the French call it, la petite mort: the little death.

Desire can also drive us toward a deeper understanding of ourselves. In her seminal essay The Uses of the Erotic, Audre Lorde frames eroticism as a lens through which to interpret other aspects of our lives—a tool of self-knowledge—evaluating, honestly, what brings us meaning. In other words, the transcendent joy we experience through sex can disrupt the status quo, drawing awareness back to the intrinsic pleasures that make us feel whole.

“As humans, we’re always chasing euphoria, always seeking a release. We want to experience something greater than the body, greater than the mind,” says Tali. “Of course, those states aren’t sustainable; you can’t live there. But it’s the time we feel most alive.”

Camille Sojit Pejcha: Your work seems to continuously deal with these themes of inner and outer selves, and the space between. How did the visual iconography evolve?

Tali Lennox: It’s interesting what comes out in my work, because I don’t preconceive the ideas—I work from intuition and allow this whole tapestry of motifs, visions, and feelings to emerge. Afterwards, there’s this process of unpacking what I might have collected externally, sometimes from years ago.

I noticed portraits of women’s insides in your older work—the organs, guts, viscera. They felt erotic in a strange way.

I was inspired by the anatomical wax Venuses created by medical pioneers in the eighteenth century. They would have their stomachs open, revealing wax organs to teach medical students about anatomy. They were beautiful, like Sleeping Beauty. I was struck by the combination of morbidity and eroticism. I like thinking about the inner world as a treasure chest, or a jewellery box. That’s why, in my paintings, the organs are iridescent and alive, almost twinkling. I wanted it to feel full of energy and beauty, to show what a miracle the body can be.

In this new show, there are paintings of figures in animal masks. They seem a little devilish, almost fetishistic, like they’re beckoning you into an alternate reality. What do they mean to you?

When I began these paintings, the words ‘Carnival of the Mind’ kept echoing in my head: all the characters, monsters, and figures inside us since childhood. Masks symbolise escapism and transformation, hiding and escape, but also the wonder of creating worlds inside and outside ourselves.

It reminds me how, through sexual roleplay, people use objects as tools to channel a cultural archetype—they become a mother, an authority figure, a worshipper.

Yes. Through sexuality, people enter this place of “fantasy,” but what it really means is that you can perform as somebody else, acting in an alternate energetic field. Healers, like shamans and witch doctors, have also used masks historically. They’ve always been a medium for accessing archetypes and spirits.

I was just talking to a woman who doesn’t drink. She told me, “Alcohol is called ‘spirits’ for a reason—you’re ingesting another force. When you go to parties, don’t think about yourself. Be curious and look around, and you’ll see people transform into these archetypes: a mermaid, a jackal, a devil.” That’s also what I was thinking about with the mask paintings: They’re sort of submerged, seductive, a bit frightening—there’s a sense of giving into these darker temptations and how, in bringing another spirit into us, we transform.

What’s another experience or object that found its way into your work?

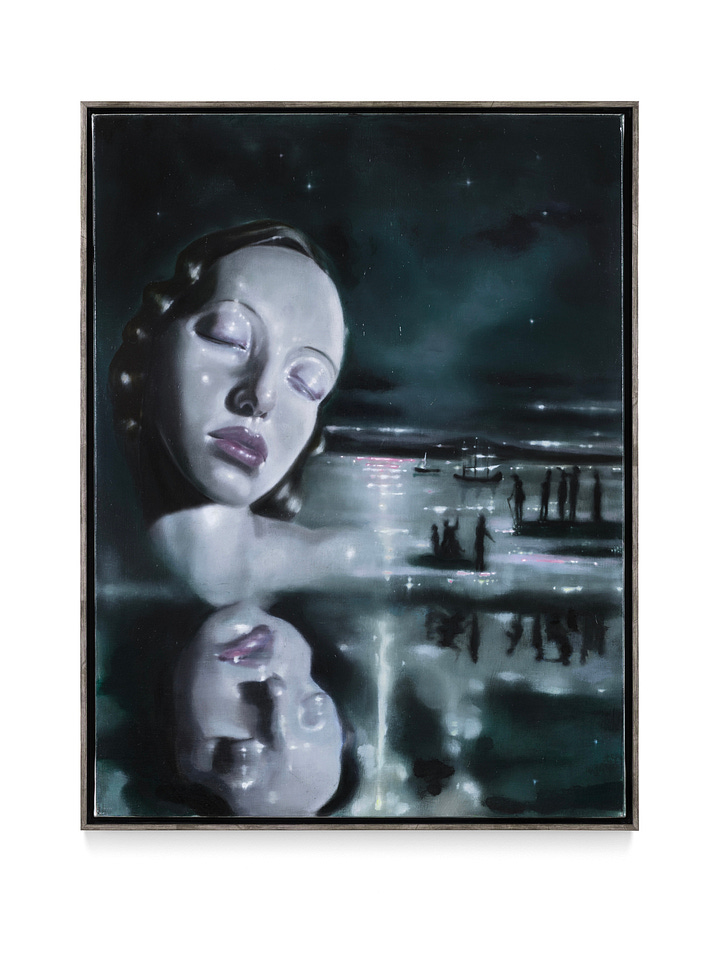

A couple of years ago I visited the Roman baths in Bath, England—the only natural hot spring. The ruins are incredible, and when you learn about the functions, it was basically a bathhouse. And in the museum, they had this big gold head of Sulis Minerva, the goddess of the spring. The head was once part of a massive statue, placed in the baths with candles lit around it 24/7. People prayed to her. Then, in the 1700s or 1800s, someone found the head in a ditch. That journey of an object—that’s why I love relics. They carry potency and meaning through time. Sulis was both the goddess of the spring and curser of dreams.

That’s fitting, given what you told me about yourself as a child—that you used to find yourself stuck in the state between waking and dreaming. What did that feel like?

Similar to what it feels like to go mad, really. You know, when you see someone on the street who’s in another realm, I’m always curious: What are they seeing?

When I’m working, there’s a lot of isolation. There’s such an interesting energy one can tap into when you’re not exposed to distraction, and you let the imagination illuminate itself. There are frequencies you feel you can almost touch yourself and hold, yet they might not exist at all. It’s this moment of breaking down—or breaking through—into another dimension. Because that’s the question: Are you breaking down, or breaking through?

I think a lot about William Blake. He was seen by most as a madman in his lifetime because, as a child, he began to experience visions. Once after a solitary walk in South London, he told his dad he had seen a tree full of angels, and he wanted to beat Blake because it sounded so offensively far-fetched and loaded within his religion. But maybe it’s an opening to something else, something far beyond religion.

It’s no coincidence that a lot of great artists and thinkers were thought to be mad.

Yes. I also read a book about Blake recently, and learned that he created a large collection of erotic and sexual artworks that tragically are believed to be destroyed. His connection to free love and nature—that may have been influenced by his mother, who was part of the Moravian Church sect. They believed access to God came through sex and ejaculation. When initiated, you’d have sex with your partner on the altar, surrounded by the congregation. It was seen as a divine connection.

It’s so interesting how some spiritual traditions see orgasm as a release of energy that fuels creativity, and others believe in keeping the power within. To you, what’s the relationship between desire, art, and spirituality?

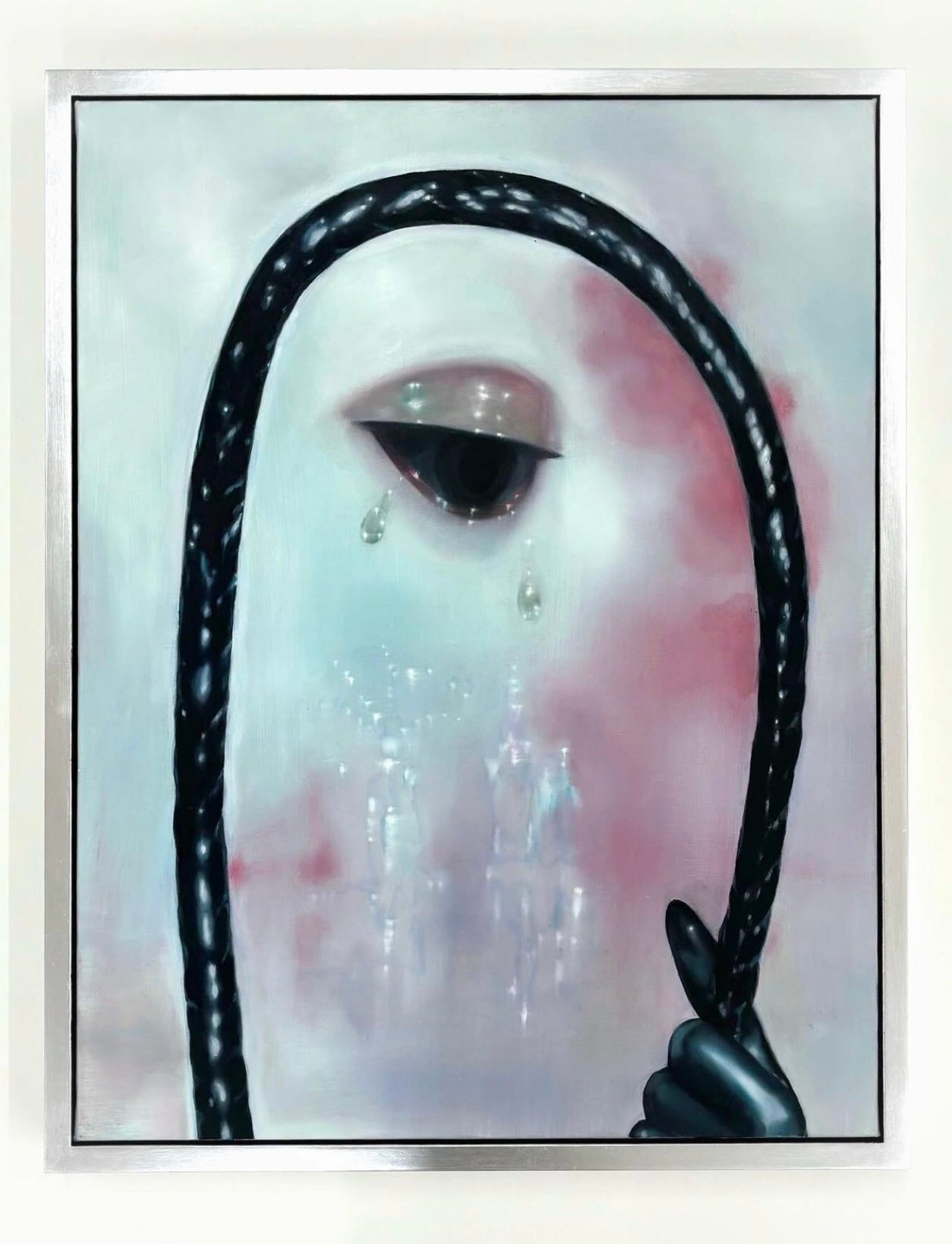

With painting, you often want to depict your desires. For me, that includes images of higher powers in the sky—eyes, tears, symbols of being held. It’s about digesting a time where so many feel powerless, and acknowledging that across history, there’s always been something greater than us. It’s a confusing time; even from a safe place in the West, you can open your phone and see images that are unspeakably tragic. I think what one can do as an artist, in a small way, is transmute empathy—tap into something deeper than the surface.

The first time we talked, you described painting almost as a riddle, something that provokes feelings people don’t fully understand. It reminds me of how good art, like good sex, has that transformative quality—the ability to unlock something in you.

Yes. The paintings, for me, are often attempts to return to those openings, those feelings of something greater than words. That’s why I love painting tears. To me, tears aren’t about sadness. They’re expressions beyond language — they literally expel from us. They can hold joy or sorrow. They’re these breakages where emotion exceeds what can be said.

Can you recall a moment of breakage or rupture in your own life that pushed you in a different direction?

I was in a river accident where I almost drowned. After that near-death experience, my paintings completely transformed. Before that happened, I was always painting portraits, which, you know, it’s fun—there’s a lot you can get from somebody’s face, but it is literally surface. Now I’m in this different role; I started painting imagination, painting symbols. And so that experience quite literally allowed me to take from a space that was deeper into the psyche, from that experience of breaking open.

Like most people, I’ve had experiences through tragedy or ecstasy that have shaped my time on this planet. I’m always trying to return to those states. As humans, we’re always chasing euphoria, always seeking a release. We’re also trying to leave reality, to have these moments of rupture that open into something greater than the body, greater than the mind. That’s not sustainable; you can’t live there. But it’s the time we feel most alive.

For me, painting is always that space where realms meet. Some of the paintings in this series feel like fever dreams. And personally, I love having a fever.

Why? Because it’s psychedelics-lite?

Yeah. I was recently really sick, and afterwards, I felt this pure bliss. It’s why people go to bathhouses or saunas or cold plunges—these are catalysts that bring you into heightened states.

That’s also what we seek through sex.

Exactly. You can’t live in climax, in eruption. But everyone’s chasing that peak. The aftermath can be chaotic, but those euphoric moments are the essential human experience—they’ve been with us through all time, in cycles.

Within myth—or even in these places we go, like bathhouses—we seek internal realms that can feel so dreamlike and expansive, where we can merge the interior with the exterior. It’s a transformational, in-between place, like being between worlds. For me, painting is a way of staying close to wonderment. It’s a flow state, where something reveals itself to you.

I used to be obsessed with flow state. There are studies that show that thinking about yourself and how you look can block flow, which is something you want to retain during sex.

Exactly. That’s why I love painting—nobody’s looking at you.

Sulis & The Wreck is on view in Geneva through September 11th, 2025. You can read the first edition of Figure Study—an interview with the legendary porn star, parliamentarian, and cultural icon Cicciolina—here.

always so insightful 🌙

this is such a wonderful interview. and now i’m a tali lennox fan!