The Whore, the Girlboss, and Elena Velez’s America

In a conversation on sex work, desire, and transgression, Camille gets the inside scoop on the designer's collaboration with OnlyFans—and attempts to get to the heart of her incendiary politics

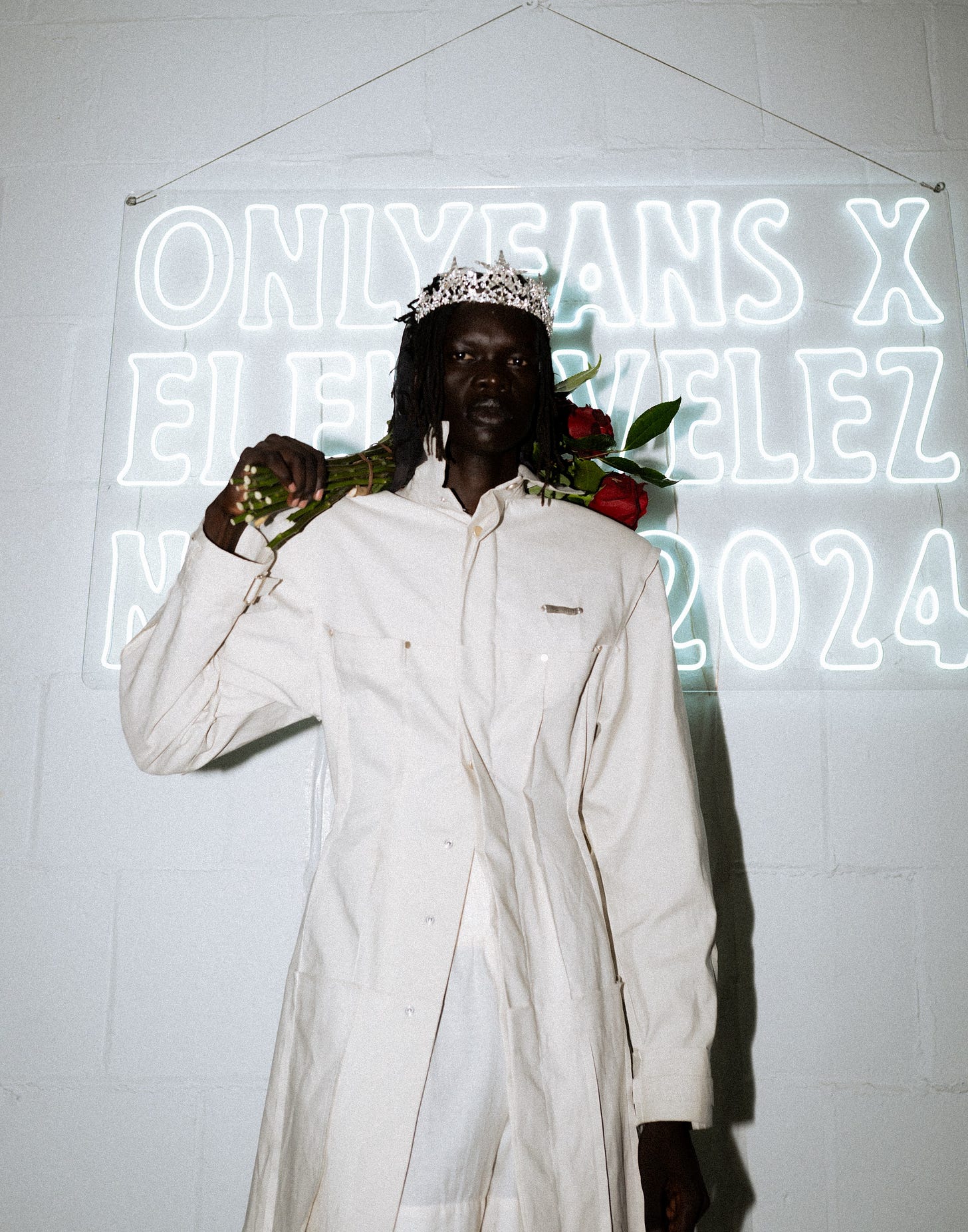

Elena Velez has been described as “a rare talent,” “fashion’s problematic fave,” and the “Donald Trump of emerging designers.” She’s staged controversial Gone with the Wind-themed literary salons and held muddy wrestling matches in lieu of runway shows. And this season, she embarked on a collaboration with an equally controversial collaborator: the adult content behemoth OnlyFans, who made its first foray into the fashion industry as the sponsor of her Spring/Summer collection “La Pucelle.”

Drawing inspiration from the likes of Lady Columbia, the Statue of Liberty, and Joan of Arc, Velez aimed to build a “portrait of American aspiration” through the symbolic feminine figures that come to represent countries in times of revolution. She’s interested in exploring feminine archetypes, and sees the OnlyFans girl as a mirror to the American girlboss: an “intrepid, industrious women” who is “using all the tools of femininity, including sexuality, to improve her station.” Velez can relate: raised working-class in the Rust Belt, she’s worked hard to become an award-winning designer whose clothes have been seen on celebrities like Charli XCX, Caroline Polachek, and Rosalía. Though at this point, her provocative politics threaten to overshadow her designs.

Velez has positioned herself as the Red Scare of the fashion industry, claiming to be “apolitical” and “equally irreverent to the left and right,” even as her anti-woke posturing acts as a dog-whistle to conservatives. At the same time, she says she’s been misunderstood by the press—which would be easy to do, because while she’s a champion of free speech, she’s refused to define her personal views. This “radical centrism” has allowed her to have her cake and eat it too—attracting controversial collaborators like Anna Khachiyan, Dasha Nekrasova, and the alt-right comedian Sam Hyde, while also offering a thin veneer of plausible deniability everybody else.

I really want to love Velez. I think she’s a refreshing talent, and I agree that the fashion industry is due for a shakeup—or, as she puts it, “a cultural defibrillator” to jolt us out of our complacency and the creative malaise of overcommercialization. But while the risks she’s taken in the realm of couture have paid off, I’m skeptical of the reactionary, post-woke politics she’s come to symbolize. And I think the fact that she’s successfully framed herself as a rebel and political dissident—while simultaneously refusing to take a clear stand on anything, or engage too deeply with the ideologies her project attracts—speaks to the state of the culture right now. People are fed up, disenfranchised, and so hungry for transgression that the idea of someone speaking truth to power is compelling. And in giving voice to our collective dissatisfaction, Velez appeals to a wide range of people, from alt-right extremists to disillusioned liberals. This is what makes Velez, like Trump, a symbol of the times: a moment when everyone’s eager to overturn the status quo, but we can’t seem to agree on what it is.

After attending her runway show with OnlyFans, I wanted to understand how Velez—a 30-year-old mother of two, born to a Puerto Rican father and raised by a working-class female ship captain in the American Midwest—came to serve as an emblem for conservative politics, and what she really stands for when the chips are down. In the below interview, I attempted to elicit answers about what she believes, withholding my commentary and focusing on the lived experiences that underpin our differing world views. I encourage you to read through and form your own opinions.