The Secret History of the Chelsea Hotel

Photographer Tony Notarberardino joins me to discuss the erotic heydey of Hotel Chelsea, the ghosts that haunt its halls, and the untold stories behind his wildest portraits

Happy Halloweekend!

In the spirit of the season, I’m writing to you with a spooky special edition of Figure Study, the art column I co-publish with Elephant Magazine. It’s an intimate conversation with my friend Tony Notarberardino about the erotic history of New York’s Chelsea Hotel, which he’s been living at and documenting for 25+ years.

From famous basketball players jerking off to Helmut Newton to twincest, sex parties, and rooftop burlesque shows, Tony regales us with the true stories behind his wildest portraits—and what it was actually like to live in the Chelsea during its illustrious heydey, with Dee Dee Ramone as a roommate. I recommend clicking through to read this post on the website, as it’s too long for email and you don’t want to miss even one of these photos.

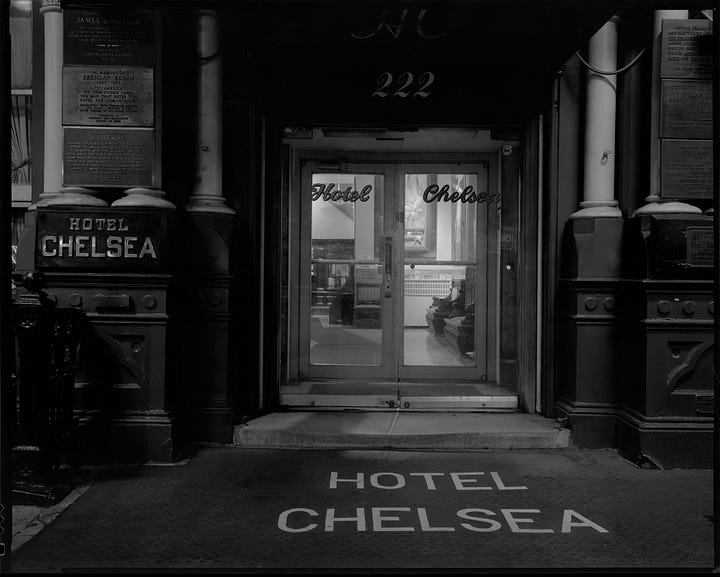

On the sixth floor of the Chelsea Hotel is a door like no other. With its brass lion knocker and technicolor paint, it stands out among its neatly renovated neighbours: a relic of another era, when the hotel housed artists and eccentrics of all stripes.

Painted by the Australian artist Vali Myers—who could be found wandering the halls with her pet fox on her shoulder—it often prompts curiosity from the hotel’s current guests, who pay top dollar to stay in a building steeped in history. “There’s not a day that goes by when someone doesn’t take a picture, or knock and ask me about it,” says Tony Notarberardino, the Australian photographer who took over the apartment from Vali in the mid-nineties. “I always try to be generous, to take them in and show them around. People are curious about the hotel’s original residents, and now, there aren’t many of us left.”

The Chelsea still attracts artists and creatives, serving as a destination for parties, book launches, and runway shows. But it’s residents like Tony—the hotel’s unofficial photographer, and unsung hero of New York nightlife—who keep its legacy alive, carrying forward the spirit of radical creativity that made the hotel a haven for artists exploring the outer limits of sexuality.

From Robert Mapplethorpe’s groundbreaking, sexually-explicit nudes to Leonard Cohen’s famous Chelsea Hotel No. 2, many of the works of art created at the Chelsea were inspired by desire. And when Tony moved in, the Chelsea still served as an erotic underground—a space where individuality reigned, and queer sexuality was celebrated long before it made it into the mainstream.

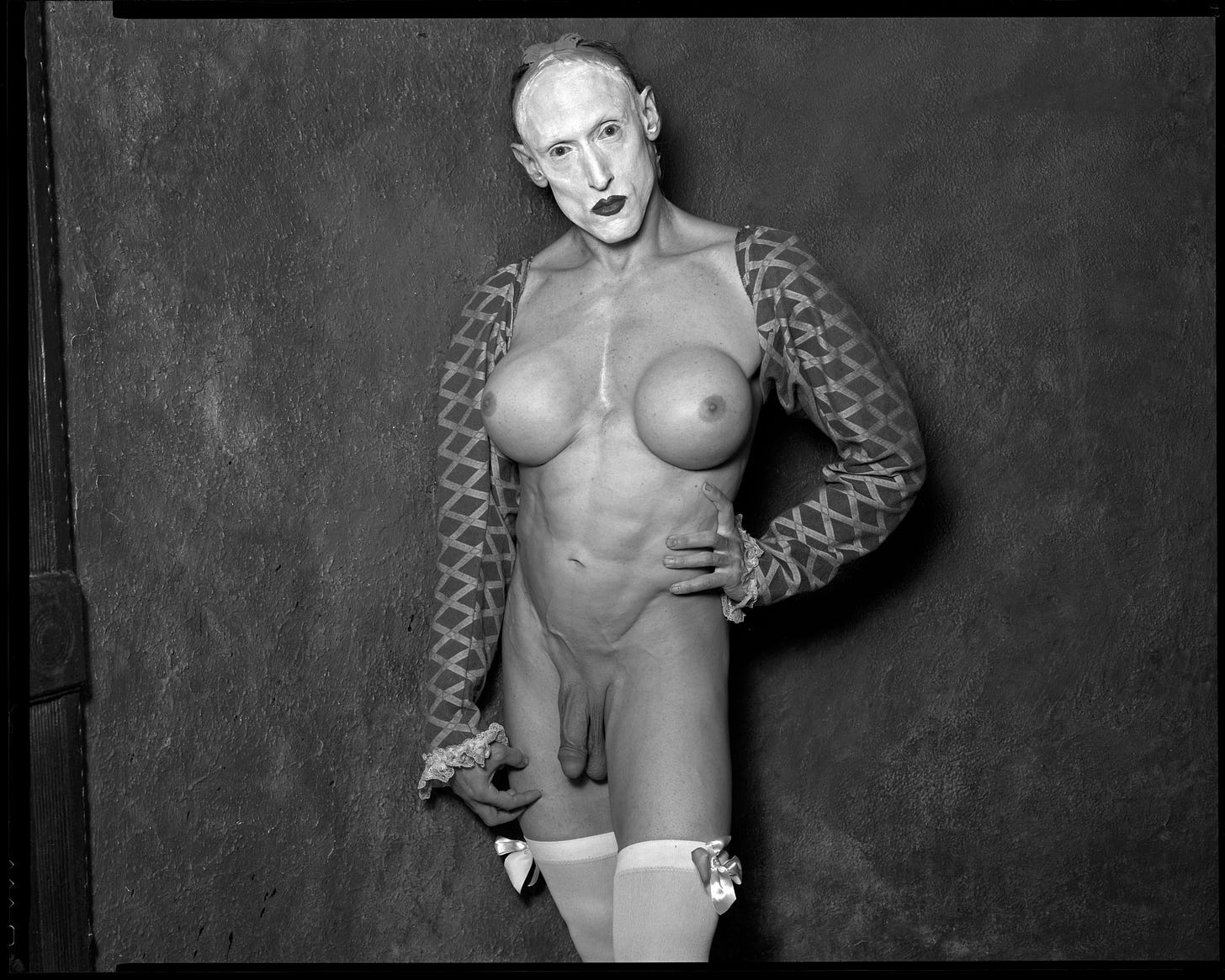

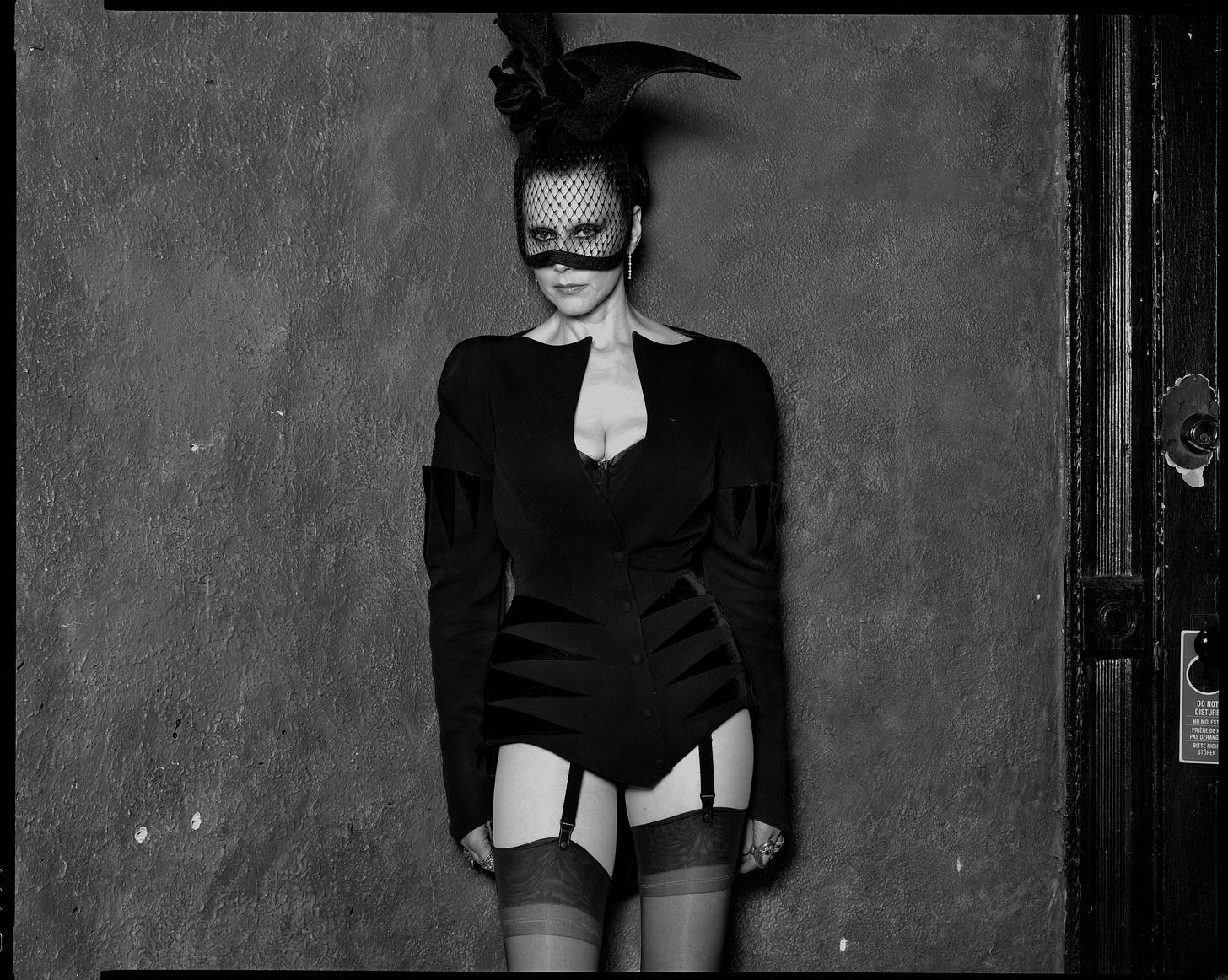

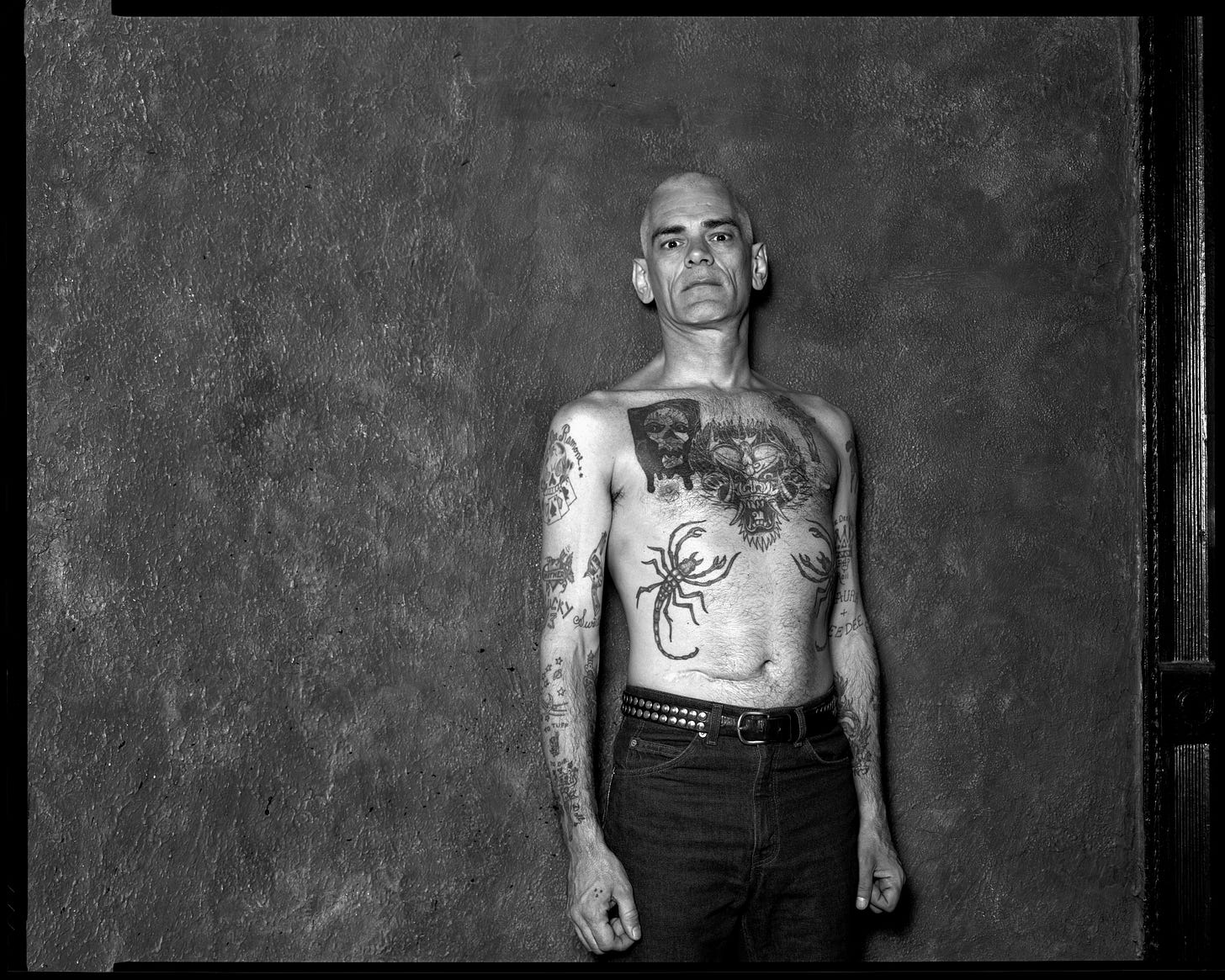

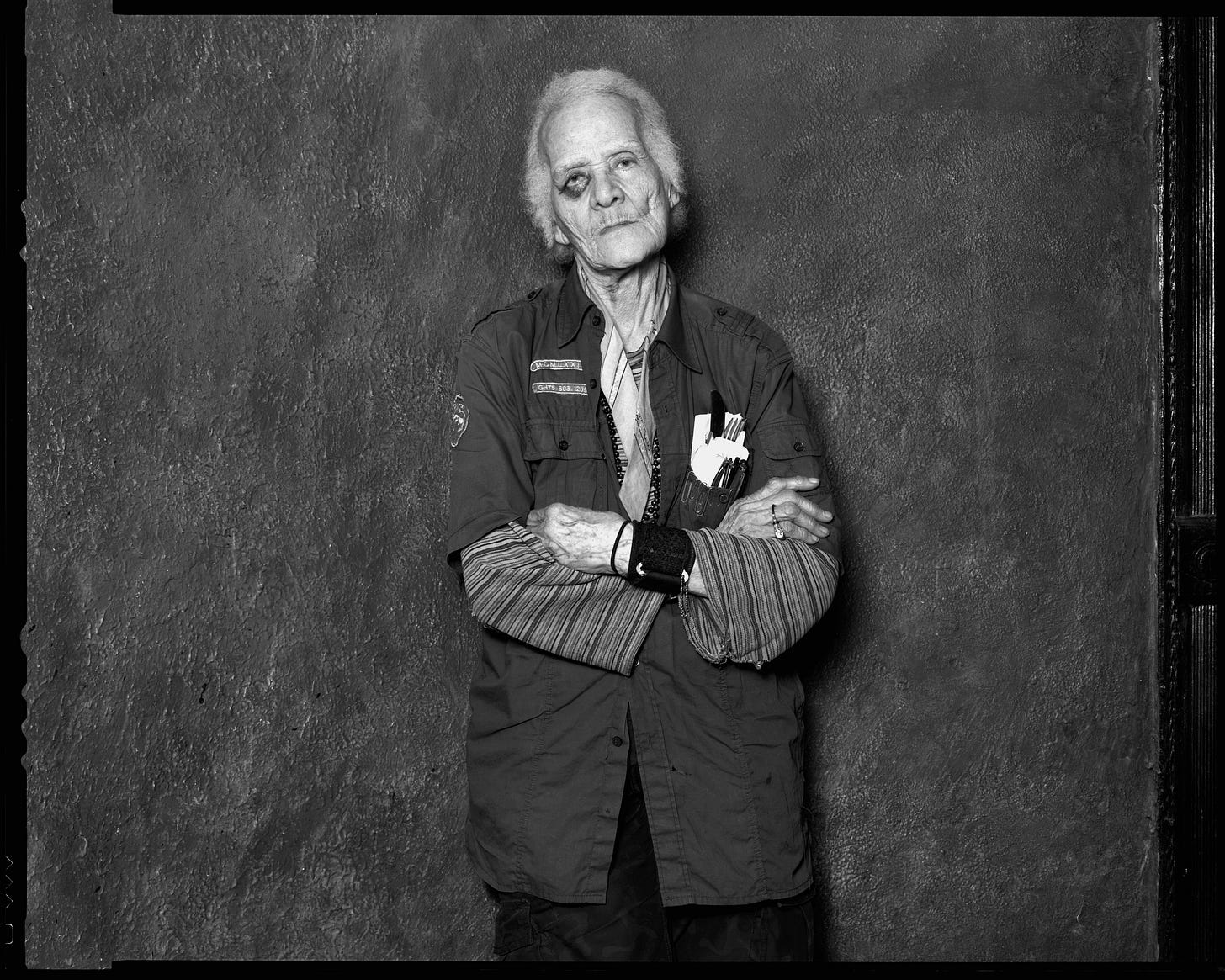

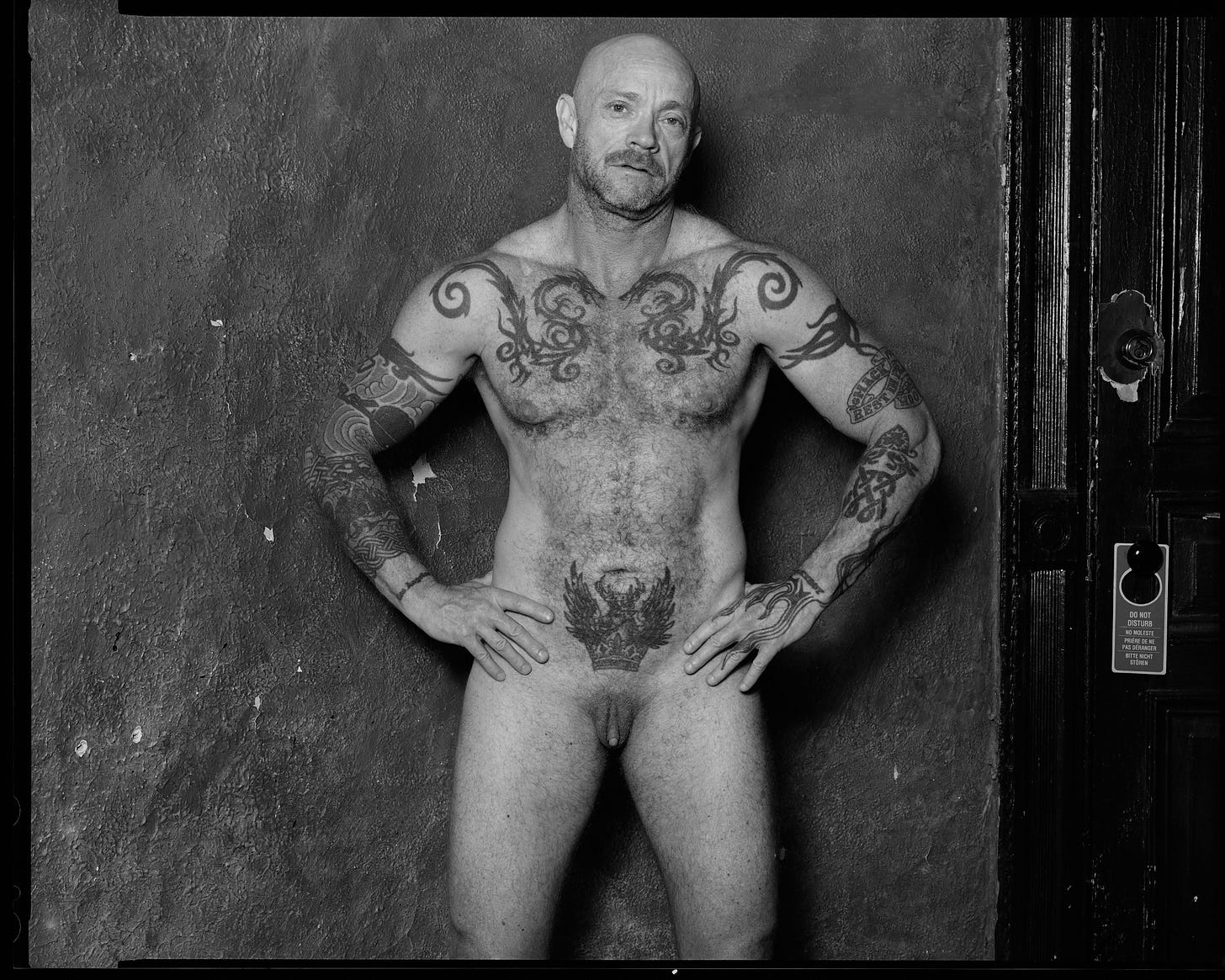

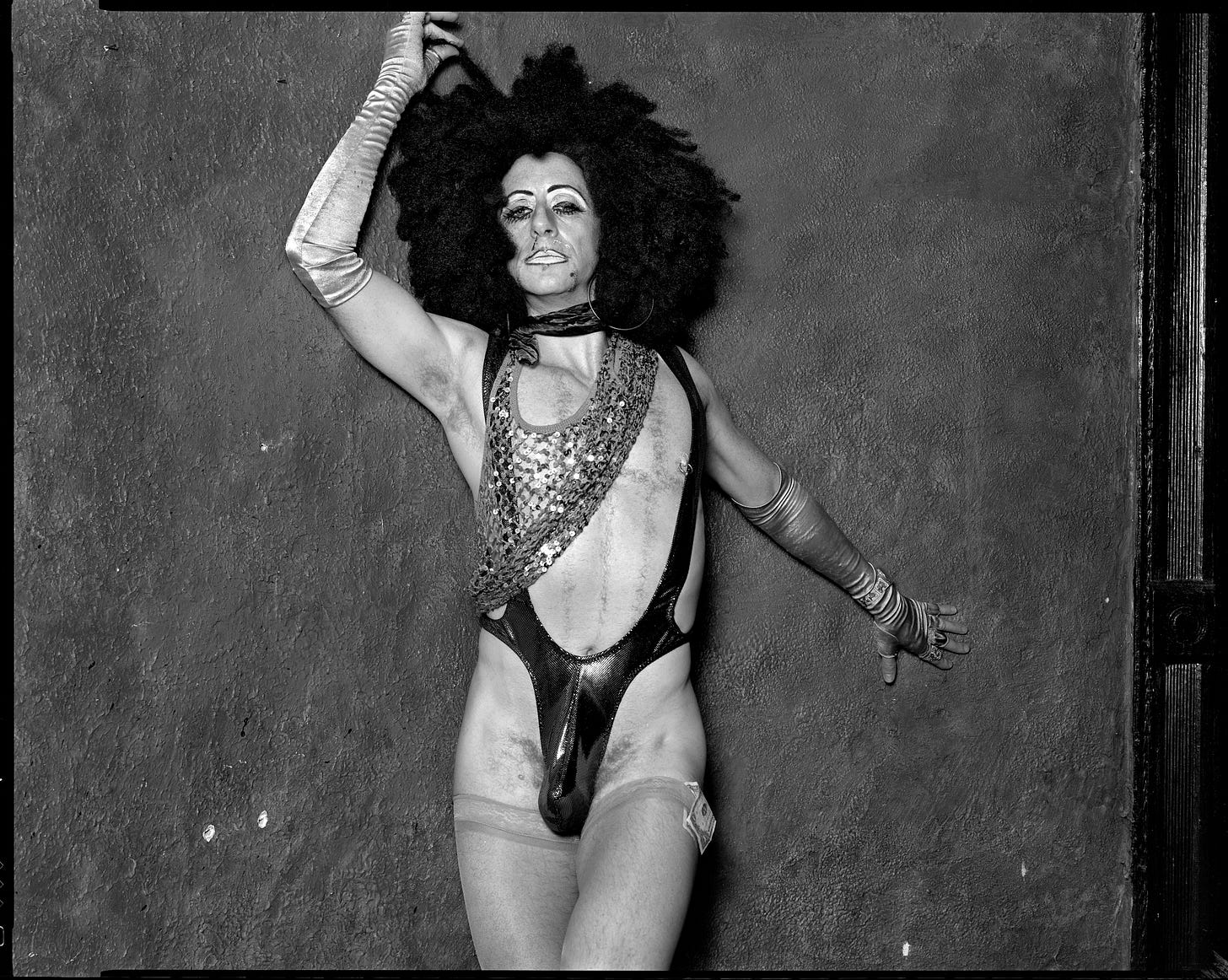

In his series ‘Chelsea Hotel Portraits’, Tony captures the spirit of the era, taking bold, black-and-white portraits of the people he encountered using a large-format, 8×10 film camera. The series features legends like Dee Dee Ramone, Arthur C. Clarke, and Debbie Harry, alongside a revolving cast of characters less talked about in the history books: dominatrixes, burlesque dancers, and escorts, who Tony photographed with as much care as the hotel’s celebrity guests.

For this special edition of Figure Study—a column co-published by Pleasure-Seeking and Elephant Magazine—Tony joins Camille Sojit Pejcha to discuss the erotic history of the Chelsea, the ghosts haunting the hotel, and how he’s keeping its subversive spirit alive after all these years.

Camille Sojit Pejcha: You’ve been documenting the Chelsea for over twenty-five years. What was it like when you moved in?

Tony Notarberardino: Back in those days, there was such a great community of artists here that was really inspiring. It’s impossible to quantify what the hotel has given the world on so many levels—different artists, writers, musicians, filmmakers. And it was like that for the last fifty years, right through the Beat Generation, the rock and roll of the sixties, punk rock in the seventies and eighties, and then the nineties.

When I moved in, there were constantly things going on—creatives living here, community discussions in the lobby, people getting together and having dinner parties. I just stepped into this world. Then I started photographing them, and that’s when the Chelsea opened up to me. Because then, you know, I’d get people over here and hear their stories, and I’d find out a lot more about the Chelsea than I ever knew.

You documented the hotel through the people, not their surroundings. Why did you choose that artistically?

Shooting in that section of the apartment, you can see it’s the Chelsea Hotel, but you don’t get any clue what my apartment’s like. That was the intention: I wanted to focus on the people who make the hotel what it is, so they were the heroes of the story.

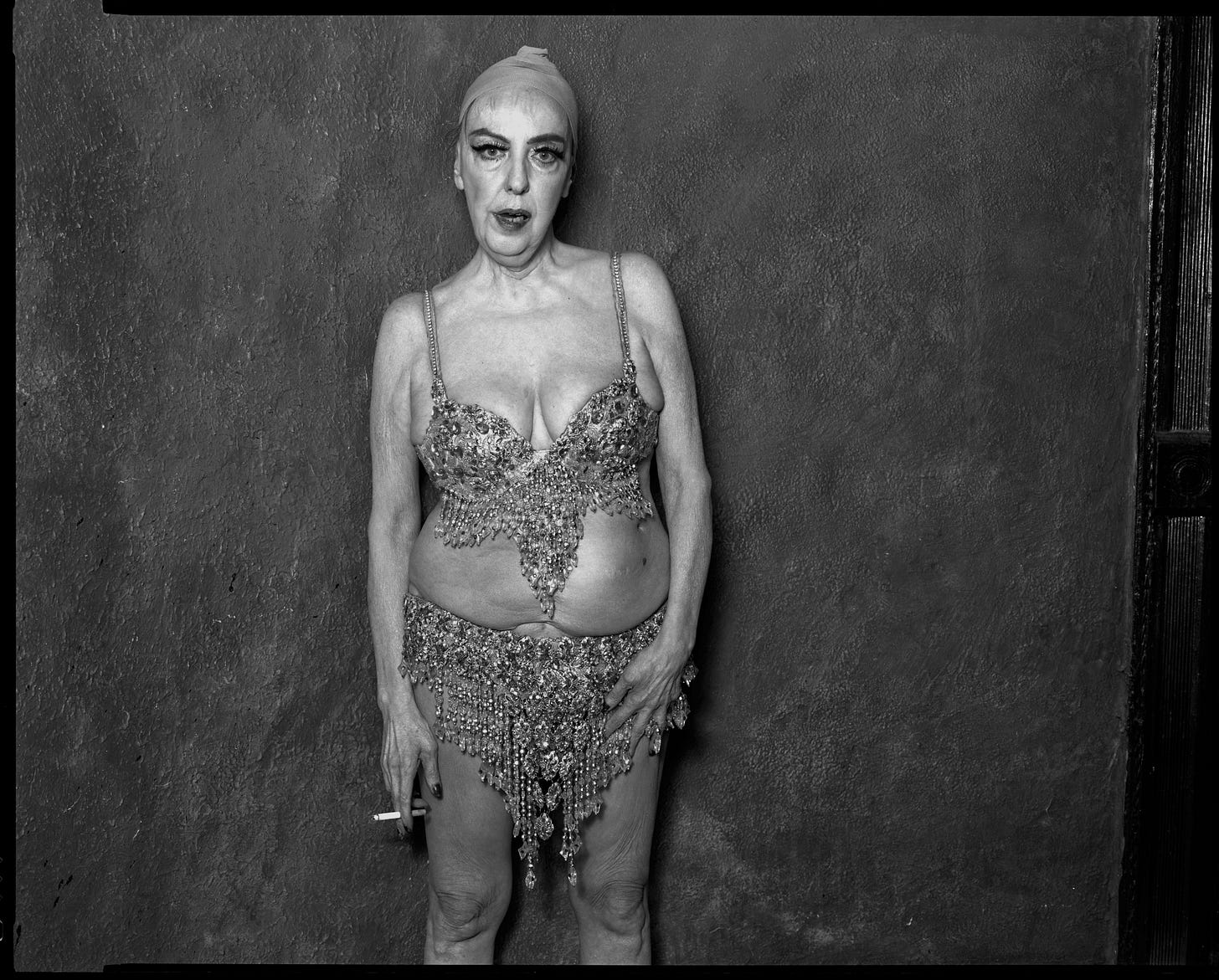

In that spirit, I think it would be great to hear a little about the people in these photos. Right now I’m looking at Bonnie, shot on Thursday, February 23, 2006, at 9:30 PM. How did you two meet?

Bonnie was the night receptionist; she lived here, and that’s how she paid her rent. Every day, she put on a big redheaded wig and spent all day getting dolled up before her shift. She was a showgirl from the 1950s, and that’s how that picture came about—it was one of her old costumes. We found it after her room caught fire. I helped her wash and dry-clean what was left of her clothes, found that old showgirl outfit, and said, “Bonnie, we have to!” To get her like that was a real coup—you never saw her without her wig.

I love that you photographed not only the celebrities and famous artists, but the staff. You also have a lot of photos of the dominatrixes, drag queens, and escorts who worked here, as well as queer icons and burlesque performers some people might recognize.

Yes—Rose Wood, for example. She lived on the seventh floor, next to Susanne Bartsch and Stormé DeLarverie. Back then, I knew Rose by another name—she was an art restorer, one of the top in her field, and mostly kept to herself. But one day, during a big drag event, she came out of the elevator with this huge wig and sparkly miniskirt. I didn’t even know who she was! I followed her out and asked for a portrait, introducing myself. She looked down and said, “You know me.” I went, “That’s you? Holy fuck!” And then she became Rose, and for the next twenty years, I documented her transition.

Didn’t you have a similar experience with Susanne Bartsch, where you knew each other but didn’t recognize her?

Yeah. When we met, she was raising her son, not doing much nightlife. Then one night, I saw her dressed up—I was in the lobby, and Susanne came out of the lift with an entourage, looking incredible. I nearly fell over backward! But to be fair, I don’t think Susanne recognized me for the first five or ten years we knew each other. Now, of course, we’re very good friends.

Except when you’re having parties.

Oh yeah—she’s the only one who complains about the noise. Her bedroom is above mine, and you know what my bedroom can be like at five in the morning…

What does she even say to you?

It’s like, “Tony, who the fuck’s your DJ? They’re playing shit music. Your bass is too loud. Can you turn it the fuck down? I’m trying to get some sleep.” I’d always get these texts and show people, and they’d be like, “Are you fucking kidding me? She’s throwing the biggest parties in town and she’s complaining about your noise?” It’s hysterical. But you know, it was all in good fun—I’d meet her in the street and she’d laugh and say, “If you’re gonna play music that loud, play some good music at least.”

We have the original floors—they didn’t replace them like in the new hotel rooms—and the walls are so thick that they actually retain a lot of the sound. Back in the sixties, the musicians used to love it here because they could play all night and no one would hear them. When I moved in, Dee Dee Ramone was living in the room next door. He called it the Australian Wing because Vali Myers was from Australia, and then I moved in.

How was Dee Dee as a roommate?

We were friends as much as anyone was—you couldn’t really get close to him because he was living this crazy life. I’d come home some nights and find him asleep outside on the doorstep, and we could get on each other’s nerves. Back then, I had a record player, and if he was making noise at three in the morning, I’d put the Ramones on really loud. I’d count down from ten, and sure enough, he’d be yelling at the door, like, “Turn that shit off!” It was a funny party trick.

The room we’re in now used to be Dee Dee’s, and before that, it was Vali’s. Do you know much about what happened here in Vali’s time?

Vali had her own universe. She attracted so many interesting people—Salvador Dali, Tennessee Williams, Mick Jagger, and Marianne Faithfull all hung out here. Patti Smith really idolised Vali; she wrote about it in Just Kids, and it was when she was living in my room that she tattooed that lightning bolt on Patti’s leg.

These days, there’s a whole new generation of people fascinated with the place because of Patti Smith, I guess, and stories and nostalgia in general. And the people who are fascinated with it are fanatics—it’s a real obsession. Not a day goes by that I don’t find someone outside my door, taking pictures of it.

I mean, that was painted by Vali, right?

The door, the murals—it was all there when I moved in. And in the elevator a couple of weeks ago, I met an old woman who said that she and her husband had walked around the hotel and were fascinated by the history. They were looking for the original apartments, and seeing doors like mine really meant something to them.

It’s a portal to that whole history.

Yes. It’s one of the oldest pieces of art created at the Chelsea that is still at the Chelsea, since so much of it was destroyed or renovated.

The Chelsea was also the home of a lot of queer icons, like Candy Darling and Stormé DeLarverie, who’s said to have thrown the first punch at Stonewall. You have a picture of Stormé here, with a black eye—do you know how that happened?

Well, Stormé’s story was that five guys jumped her, and they all came off worse—three ended up in the hospital, one punched her in the eye, the others ran off. You didn’t mess with Stormé; she carried a snub-nose revolver strapped to her leg. That was her nickname, Snub Nose 38.

You know, I’ve done a lot of interviews, and no one’s ever asked me: “Has your life ever been threatened while taking these portraits?”

Well, was it?

Yeah! Once, in the middle of the night, my door was broken down by two guys with baseball bats looking for negatives. I’d shot their girlfriend earlier that evening—an erotic portrait—and when she got home that night, she regretted doing a nude. She told her boyfriend, and these guys literally kicked the door down and threatened to bash the shit outta me unless I gave them the negatives.

It wasn’t the first time. Once I took a picture of a guy smoking crack. Turns out he was a famous baseball player, then retired. But it was known that he was a crossdresser, even while he was playing. He was here with some friends partying, and one guy pulled out a gun. He’s like, “What are you gonna do with these pictures? You’re not gonna fuck up my boy, right?” I told him, “No, this is an art project.” He said, “You’ve gotta get a release form from him.” I’m like, “Well, he’s locked in the bathroom smoking crack.” I knocked, and he’s yelling out asking if I had any porn magazines ’cause he wanted to jerk off. He opens the door asking me for something, and I don’t have anything—just a Helmut Newton book. I thought, “Oh well,” and gave it to him, which seemed to be enough.

A real art appreciator! Speaking of porn, how did you meet Buck Angel?

I met Buck when they were filming a porn movie at the hotel. I didn’t know much about him until we sat down and talked, and he told me his life story—showing me pictures from when he was a supermodel in his early twenties. And now, to look at Buck, it’s just phenomenal.

Some of these portraits were years in the making, and some took ten minutes. There’s no rhyme or reason to how it happens. Sometimes, you have to get to know someone and gain their confidence, and other times Ie just meet someone spontaneously and go, “This is what I’m doing. You interested?”

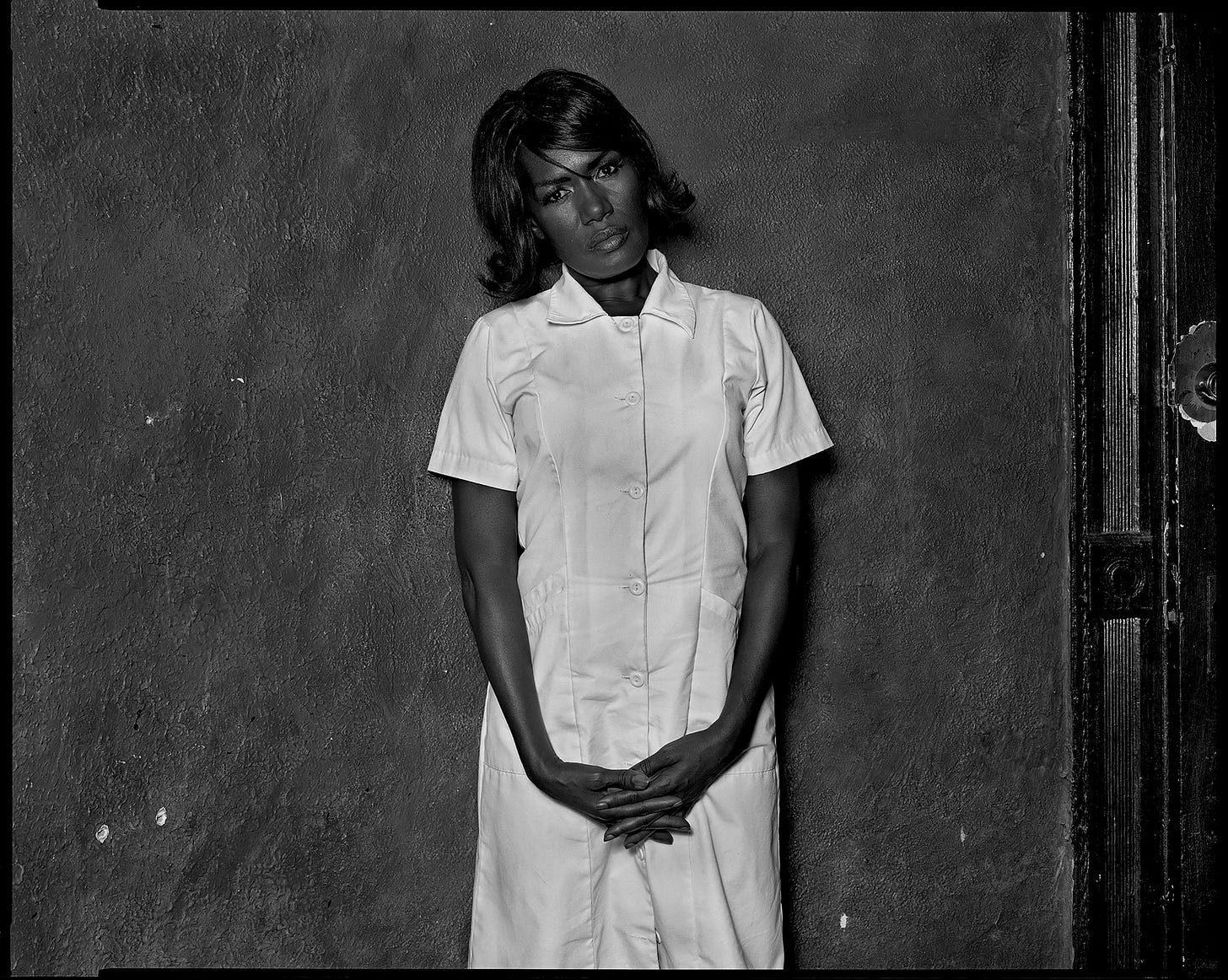

Tell me about the portrait of Grace Jones.

Abel Ferrara had moved into the hotel and made Chelsea on the Rocks with cameos of the famous stories—Sid and Nancy and all that. Grace Jones played the nurse who came to help Nancy. Back then, paramedics were often nurses, I guess.

It’s like a meta Chelsea portrait.

Exactly—like a Russian nesting doll. Grace was there because of Sid and Nancy’s story. She finished shooting at 5:00 AM and came up to my room, and as soon as I saw her in that costume, I already had the picture in my mind.

What about the Porcelain Twinz? Are they actually sisters?

Yes, they’re identical twins from Portland, Oregon. They were a big deal when they hit New York, performing at The Box and doing hardcore sex acts with each other on stage. They’ve got a fascinating story: separated young, lived apart for years, and both independently went into sex work. When they met again, they realized how much they had in common and started performing together.

I met them at a fetish party at the hotel, then shot them again around 5:30 AM. Those were pretty normal Chelsea hours. The artist community lived at night, ‘cause that’s when artists work best. And sex workers too—they all worked at night. Most of my portraits were taken between midnight and 6:00 AM. That’s why I include the timestamp, because it’s part of the story.

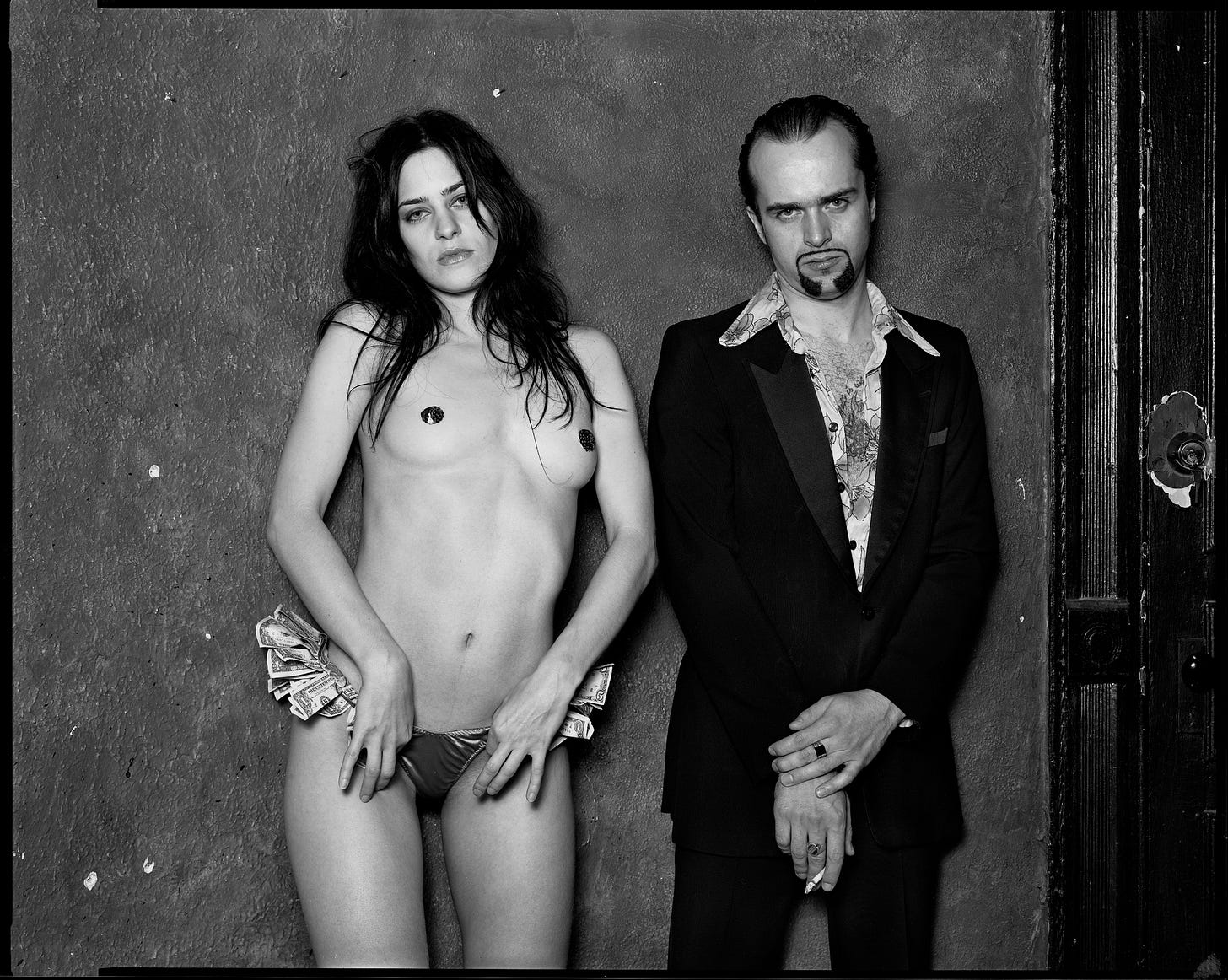

What’s the story for Franco and Manuela?

That’s one of my favorites—the stripper and the pimp. They were from Berlin and ran this club, Lesvos Vampirious, that did sixties soft-porn–inspired nights with go-go dancers, projecting old movies on Super 8 onto the girls in the cages.

Now burlesque girls get tipped with dollars, but back then it was rare. When I saw Manuela with all that money in her G-string, it stuck with me. I told her to come back to the Chelsea and leave the dollars in, because I’d never seen that before. Even now, when I see it, it reminds me of that portrait.

You also shot a lot of early burlesque icons, like James Tigger! Ferguson.

Yes, Tigger was a huge burlesque star, and he used to do sex parties at the Chelsea. I met him through Norman, who lived in the pyramid apartment on the roof and opened the Slipper Room downtown in the nineties. That was the start of the burlesque resurgence, and a lot of them lived at the Chelsea. Norman would have burlesque shows on the roof in summer, in his garden, and I met everyone through him.

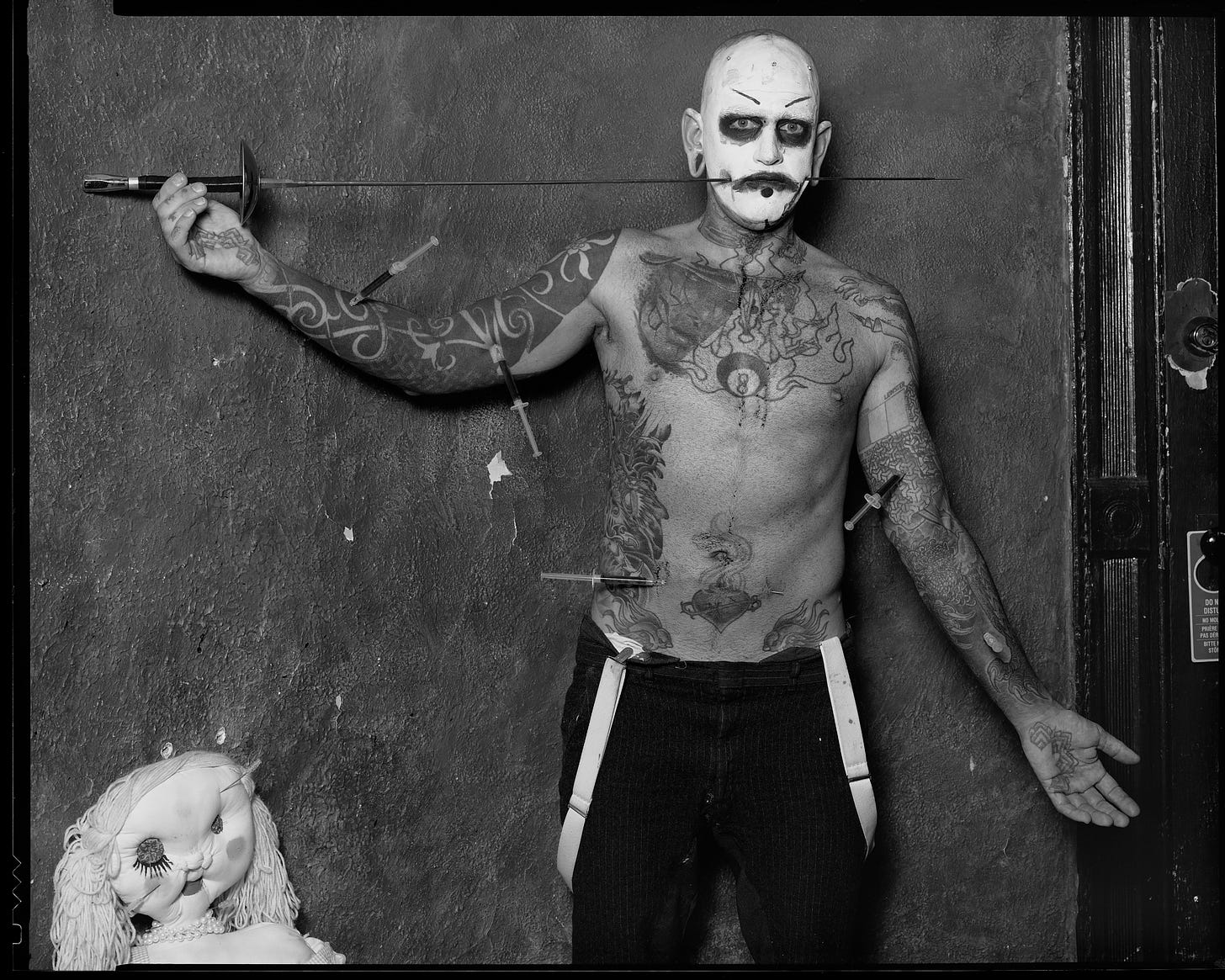

What about Damien, the one with the sword through his cheeks?

I met Damien at the Slipper Room. One night, James called and said, “Oh, you gotta come down and see this new act.” I knew it was gonna be good, ’cause James doesn’t often say that, so I went down to the Slipper Room, and it was really one of the first times I’d ever seen someone put a sword through their face. He’s lying there with fifteen-inch syringes through his arms, and I’m standing on the side of the stage looking, like, “Are you fucking kidding?” I just transcended watching his whole performance. When you first see it, it’s almost like you can’t watch it, but you want to.

And next thing I know, James is standing next to me, and he’s like, “Tony, I need to ask you a favour.” And I’m like, “What?” He goes, “That guy on stage has been staying with me for four or five days, and if he comes home with me tonight, my wife’s gonna divorce me. Can he stay at your place?” And I’m like, “That guy?The one that’s on stage putting these needles through himself?” Damien ended up staying about a week, and we became really good friends. But he was, you know, pretty crazy. He literally didn’t get outta that clown makeup. He came back from the Slipper Room all bloodied, and these guys don’t even shower. They’ve got blood on their face from the performance and clown makeup, and they wake up the next day and do it again.

That was your first time seeing that kind of sideshow act, but now you host them all the time in your living room.

Yeah, because it was through Damien that I met Anna Monoxide. Through her, I was kind of introduced to the whole world of sideshow—the Coney Island connection—which started to interest me a lot more than burlesque, because by that point, it was becoming saturated. Sideshow’s much more photogenic too; I mean, it’s so visceral.

It provokes a response.

You see it in my shows. I mean, Anna always gets such a reaction when she performs a pincushion act—some people leave the room, some pass out. It’s really confronting. Burlesque is great, but it doesn’t make you pass out, you know?

It’s one of the things that feels so true to the Chelsea’s history—that you would still have this boundary-pushing, avant-garde sexual performance art taking place here, after all these years.

That’s the spirit of the Chelsea: always pushing art, no matter what medium. This kind of performance pushes my work too, because then I photograph these people. It works hand in hand, which is the way musicians used to work. I mean, Leonard Cohen wrote that song about Janis Joplin at the Chelsea; her work pushed his along. Chelsea No. 2 was born out of that.

If they hadn’t met and fucked, that song wouldn’t exist. There’s a similar thing that happens at your parties, with so many creatives mixing and mingling. I can’t even count how many collaborations, and affairs, have started in your apartment.

You know, it’s everyone that comes there that really creates it. I just open my door and let it happen.

You really are keeping the spirit of the Chelsea alive. And on that note—and since it’s Halloween—I have to ask: do you think the hotel’s haunted?

Definitely. We always said that they can change the rooms during the construction, but they can’t get rid of the ghosts—you can’t evict them. I feel like I’ll still be here even after I die. It’s such a fabulous place that you’d wanna come back and keep hanging out.

Loved this post! Hope you don’t mind but I wanted to introduce myself. I’m a 20 year veteran of the film industry/former studio executive. About 5 years ago I started writing again for the first time since college, even sold one of my stories to Netflix. Mostly fiction, but also personal/memoir stories like this one: about my fashion photographer Dad who went from shooting Ralph Lauren’s first ads to crashing and burning at NYC’s iconic Chelsea Hotel. Introspective. Funny. Tragic. Hope you like it. My Substack is always free and I write daily about selling film rights to short pieces like this. Hope to connect!

great advise from great woman tony z